The push carts that peddled fruits and vegetables are long gone. So are the Italian nonnas who haggled with the pushcart vendors and kept a watchful eye on the neighborhood. Gone, too, are the coffee houses, cafes, and notable night spots that helped to establish this street as the bohemian enclave sung about by Peter, Paul & Mary, Simon & Garfunkel, and Bruce Springsteen. This is Bleecker Street—the central vein that runs through New York’s Greenwich Village, where, for many decades, music worshippers have made their pilgrimage.

Growing up in Greenwich Village, I attended school on the west end of this street, steps from where my great-grandparents settled at the beginning of the 20th Century. My grandmother often joked that she was never concerned with me running away from home because I was “already here.” She was right. With fake I.D. in hand, I spent many a weekend night on Bleecker Street, sipping a Sloe Gin Fizz while listening to some of the greatest performers of our generation. I was too young to know that I was witnessing history.

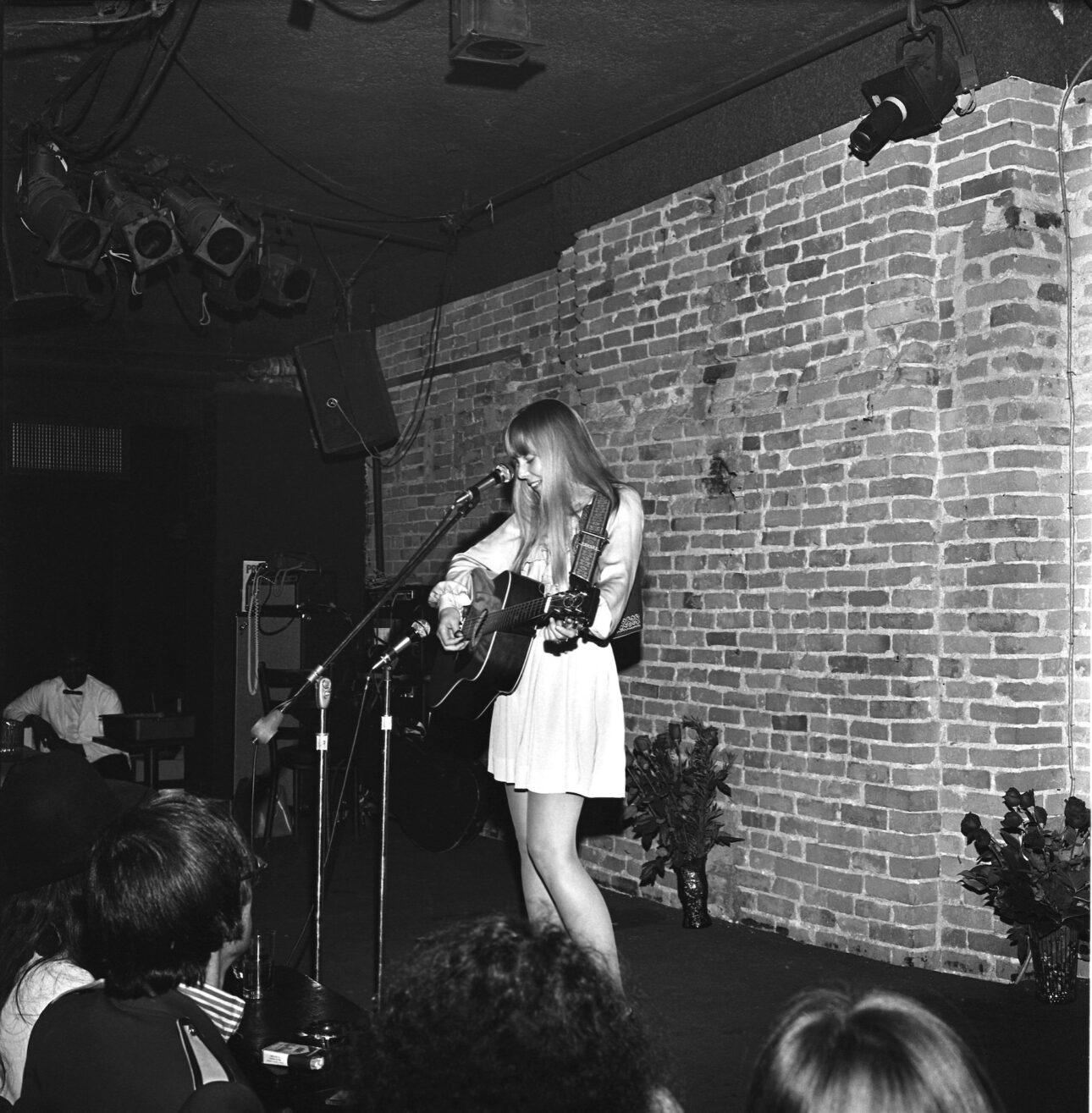

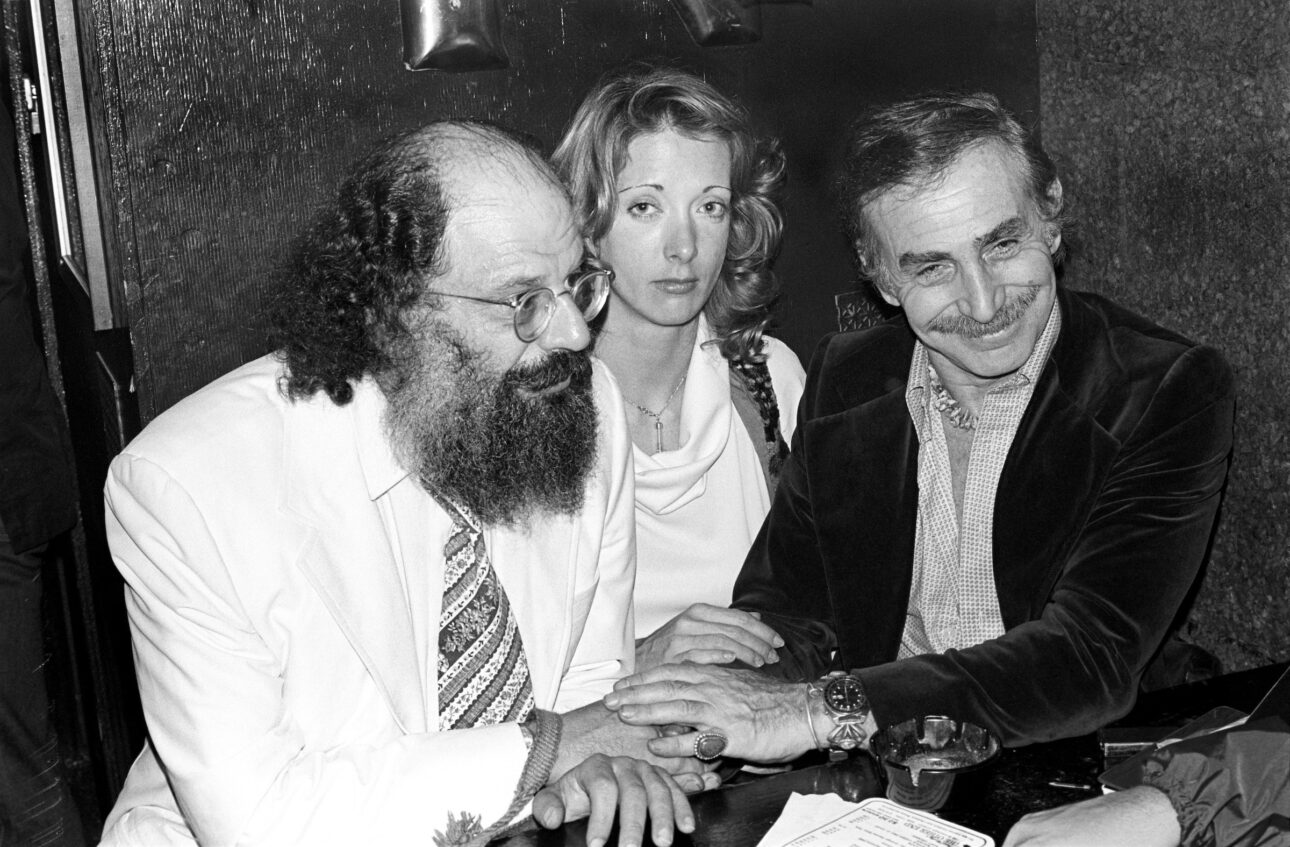

As Bleecker Street institutions like The Village Gate, The Gaslight Cafe, and Kenny’s Castaways eventually closed their doors, the musical mecca at 147 Bleecker Street somehow passed the test of time. The Bitter End, originally opened as a coffeehouse by club-owner-cum-film-producer Fred Weintraub in 1961, attracted a phalanx of young musicians needing to be heard. Joni Mitchell, Bob Dylan, David Crosby, Donny Hathaway, Stevie Wonder, and Patti Smith found their way there, and so did then unknown comedians Joan Rivers, Albert Brooks, and Steven Wright. Even I had a moment of glory on that stage, appearing with a fledgling comedy improv group in the early ‘80s. It’s no wonder nostalgia hit me extra hard when I revisited the room, this time to meet with the club’s intrepid owner, Paul Rizzo.

Save for the smoke-filled atmosphere that disappeared with Mayor Bloomberg’s 2002 smoking ban, little has changed inside The Bitter End since the 1970s. Though it’s 3:30 in the afternoon, it’s “magic hour”—that brief period of time when the room is empty, dark, and quiet, yet alive with the anticipation of the night ahead.

As I make my way down the long wooden bar toward the back of the room, I see Rizzo on a couch below an old poster advertising the Linda Ronstadt-fronted trio Stone Poneys. I immediately feel the ghosts of performances past prompting me to ask Rizzo how his past led him to his present.

“I used to come here when I was in college back in the ‘80s. I’d come into the city, do a couple of the clubs on Bleecker Street—Bitter End, Kenny’s [Castaways], Village Corner—then go to Wo Hop’s, pick up like $500 worth of Chinese food, then go back to Stonybrook at 3 in the morning and give out the orders to people in the dorms.”

Even then, the man knew how to please a crowd. “But my friends always said I had no taste in music because I liked everything. Listened to everything. I didn’t like any particular kind of music. I used to come to see just bands in general. I loved live music.”

Stage fright prevented Rizzo, who ran lights for concerts and nightclubs on campus, from forming his own band. “I was like a section leader in high school but I never took solos because I just got nervous.”

So how did he come to own the oldest continuously running rock club in New York? It all began in 1974, when Weintraub exited and Paul Colby—owner of the adjacent The Other End—took over.

“I was a bartender at Kenny’s from ‘88 to ‘89. Pat Kenny was the operating owner of The Bitter End at that time, so the clubs were connected. I left to run my own place in Brooklyn. I left after a year, my partner stayed, and I went back to work for Pat at a place called ‘Launch’ and then started working in the office upstairs at The Bitter End. I was basically running the club, and Kenny Gorka was the booking agent. Paul Colby would come in once a week, and in July of 1993 he came into the office and said, ‘I’m throwing Pat out’ because he wasn’t running the club properly. So he asked us if we wanted to buy in. I stayed on as an operator, and when Paul passed away, Kenny and I bought his shares. When Kenny passed, I got his shares and ended up with the whole club and started doing bookings. I had another booking agent to do the weekends, but when the pandemic hit, we shut down operations for a year. Since we opened up, it’s just me. I became the face of the club, which I never was really good at because I hate that crap.”

While other clubs have folded, Rizzo has succeeded in keeping the room alive and kicking.

“Like I said, I’m shy and this and that. But it keeps my relationships with the bands. And I’m getting better quality music asking to play here, a more established level of musician. I’m getting California bands that are hearing about it too. I’m also getting these younger musicians to play in the place and bring in a younger audience into the room. I had Eric Anderson the other night, but I can’t do Eric Anderson and Steve Addabbo every night. So unless you appeal to a younger crowd, you’re going to go out of business. So you start bringing in those younger players so they understand The Bitter End and they play the stage and they feel the vibe and they wanna come back and they enjoy the room.”

What does the Bitter End audience want to hear?

“Music is like art. It’s very subjective. Because I was a singer, I try to book things that are melodically good, so I listen for that. And I’m a Deadhead so we got a bunch of that stuff too. I’m into fusion and jazz, so that gets in here as well. Last night, I had the Kidbrass Sessions. It’s all jazz. All young kids. So if I’m putting Eric Anderson on the stage, I’m going to have everyone in their 60s drinking tea and soda. And if I put this other band on the stage, I’m gonna have everybody 21 drinking tea and soda.”

“Has everyone stopped drinking?”

“The going-out attitude has changed. There’s a lot more pot smokers than there used to be because it became legal. And then the younger crowd is drinking at home before they go out, so they’ll buy one or two drinks and not spend a hundred dollars because it’s an expensive endeavor to go out. A lot of the older people have stopped drinking. But also the generations coming up don’t drink as much. But you gotta get the younger kids in to know about the place.”

I ask Rizzo what he attributes to the longevity of the club.

“Two things. First, we’ve never really tried to be anything but what we are. Second is the continuity of the whole thing. If you walk in here 20 years after being here, it’s the same. And that’s what people want because they’re coming back to live that same experience that they had before. I don’t have televisions because that would ruin the whole vibe. We just stayed the path. Location has a lot to do with it as well. It helps that I’m on Bleecker Street.”

The hallowed hall on Bleecker Street begins to come alive as the sound engineer brings up the house lights and sets the stage. Like magic, bustling bartenders appear. A blast of cold air moves through the club as the front doors open to load in the first band of the night. Rizzo looks at his watch, telegraphing our meeting must come to an end.

I linger a bit, suddenly understanding Peter, Paul & Mary’s revised lyric to Elizabeth Cotten’s “Freight Train”:

“When I die, please bury me deep,

Down at the end of Bleecker Street…”