We independently evaluate all recommended products and services. Any products or services put forward appear in no particular order. if you click on links we provide, we may receive compensation.

You’d be forgiven for thinking that it’s only in the last 10 years that watches got smart. Calorie tracking, GPS, wifi-enabled poo emojis… it’s been a period of rapid wristed development. But all this didn’t start in the 21st century. Watches – proper, mechanical watches – have been helping us measure the world since the 1800s.

A watch with a tachymeter scale is a prime example. It’s a numerical scale either printed around the edge of the dial or engraved into the bezel and it lets you measure your average speed over a known distance. (They also increase the testosterone on your wristwatch by at least 100 per cent.) You could technically use one on a standard time-only watch, but for proper use they need the ability to start and stop timing, so you pretty much only see them on chronographs.

And they date back almost as far as the chronograph; 19th century pocket watches with a tachymeter scale are fairly well documented. Certainly by the 1930s, several brands were producing wristwatches with tachymeter scales, as well as the other two main measurement scales that can be added to a chronograph: a telemeter for measuring distance and a pulsometer for measuring a patient’s heartbeat.

Until the advent of digital calculators the tachymeter represented – in theory, at least – a practical and functional tool, assuming you or your co-pilot could operate it accurately enough at 80mph. As the golden age of motor racing began, in the late 1950s, and the chronograph became a must-have sports watch (think Carrera or the Rolex Daytona), the tachymeter migrated to the steel bezel and took on a technical, instrumental aesthetic that it has retained ever since.

To this day, a tachymeter has the power to make your chronograph feel innately more useful. And hopefully, by the time you’ve finished reading this, it’ll be more than just macho ornamentation.

How To Use A Tachymeter

So, the question you’re waiting for us to answer: how do you actually use a tachymeter? It’s a lot simpler than it might look, and all depends on the basic relationship between speed, distance and time. As you’ll no doubt remember from school maths lessons (stay with us!) if you know any two of those, you can work out the third.

A tachymeter is designed primarily to calculate speed – by measuring the time it takes you to travel a known distance. So it stands to reason, if you’re trying to work out your speed with a tachymeter, you need a reliable distance to work from. Mile markers on a highway work perfectly, but in their absence you can work from other distances – you’ll just have to do some mental calculations at the end. Resist the urge of your maps app…

How To Measure Speed

Start the chronograph as you pass your starting point, and stop it when you’ve travelled the distance you’re measuring over. The seconds hand will be pointing at the tachymeter scale: read it off and that’s your average speed.

The neat thing about the maths behind a tachymeter scale is that it works in exactly the same fashion no matter what you’re measuring. The thing to remember is your units of speed and distance have to match.

If you measured your time over a mile, it gives you your speed in mph; the same is true for kilometres.

If you’ve measured your speed over a longer distance, there are a couple of things to bear in mind. If it takes more than a minute, your chronograph probably won’t give you a number to work with – only a few tachymeters have a scale that doubles round past 60. So that means you either need to be going reasonably fast, or measure your speed over a shorter distance instead.

For example: measuring your speed over 100m; if that takes a sprinter a highly respectable 10 seconds, your chronograph seconds hand will be pointing at 450. But he hasn’t run the race at a speed of 450km/h – you need to divide that by 10 (1km being 10 x 100m). Therefore, your athlete actually travelled at an average speed of 45km/h. That sounds more like it.

Similarly, you could be measuring your speed over three miles – let’s say you’ve got reliable markers for that as your Eurostar speeds between Calais and Paris. It takes 58 seconds, which gives you a readout from the tachymeter bezel of 62. But you need to multiply that by three, to account for the longer distance, meaning you’re actually clicking along at an average of 186mph.

A note on accuracy: your measurements are only going to be as sharp as your timing – starting or stopping the chronograph half a second early or late will have an impact on your calculation. But down at the more realistic end of the spectrum – say, under 200mph (and we’re going to assume you’re still on the Eurostar here), it’s possible to be reasonably accurate. The slower you’re going the more accurate your measurement should be – as you can tell by looking at the scale.

Measuring Distance

It’s not quite the intended purpose, but you can use a tachymeter in reverse to measure distance. You will need to be sure you’re travelling at a constant speed though; a tachymeter only measures average speed so to use it in reverse, your speed needs to remain the same for your measurement to be accurate.

Assuming that’s so, start timing. When the seconds hand lines up with your speed, then you’ve travelled a mile (or a kilometre, as before). And also as before, you can double this or halve it as you like.

Measuring Other Things

Perhaps not as applicable to the average chronograph owner, unless you happen to be conducting a time-and-motion study of your local factory, you can also use a tachymeter to measure production of anything over a given period.

Simply stop timing when one unit has been produced, or painted, or whatever it is. The readout from the tachymeter tells you how many of those can be done in an hour.

The Best Tachymeter Watches

Rolex Daytona

One of the ‘holy trinity’ of 1960s sports chronographs, the Daytona would be a different watch without its tachymeter bezel. Over time, the details have changed, and are some of the easiest ways to tell different Daytonas apart. Examples include adjustments to the calibrations of the scale, and a shift from displaying the numerals horizontally to radially; most recently, the Daytona 116500LN received a ceramic upgrade to its bezel, making it more resistant to scratches.

Omega Speedmaster 57

If you’re after a chronograph that’s built for practical use, the Omega Speedmaster is about as good as it gets. The layout is one of the clearest, and in its purest form, there’s precious little ornamentation. This reissue of the very first Speedy, from 1957, is faithful to the original and stands out for its broad arrow hands. Tachymeter-wise, it also reverts to the engraved steel bezel rather than the more common white-on-black of the Speedmaster Professional – the one that NASA took to the moon.

TAG Heuer Monza

TAG Heuer’s pedigree in motorsport chronographs is second to none, and the Monza is one of its coolest models. Revived in 2015, this all-black version boasts a tachymeter scale as you would expect, but with a useful extra.

Working on the sensible logic that you’re unlikely to be timing cars at speeds over 200mph, TAG Heuer has used the space between 0 and 220 on the tachy scale to add in another measurement scale: a pulsometer. This – a simple variation on the same maths behind a tachymeter – lets you measure someone’s heart rate. Count 15 beats, then stop the chrono: your seconds hand reads off their pulse in beats per minute.

Bremont Jaguar Mk II

Bremont produces a lot of chronograph models, but in keeping with tradition, only brings a tachymeter bezel to the overt motoring models found in its collaboration with Jaguar. The Mk II chronograph takes its design cues from E-type dashboard instrumentation (fun fact: back in the day, these were actually made by Smiths, the last company to produce watches in England on a serious scale).

Bremont has never been one for chunky bezels, outside of the Supermarine dive watches, so here the tachymeter scale is printed around the edge of the dial.

Breitling Navitimer 01

Breitling’s Navitimer has been around since 1953 and is a true icon among watch designs. The signature feature is the use of a ‘slide rule’ bezel: a freely-rotating outer scale numbered 10-100 surrounds a fixed inner scale numbered 0-60. The third, innermost scale is actually the tachymeter, one of few that counts all the way down from 750 units per hour.

What the Navitimer bezel lets you do is convert miles to kilometers, (or nautical miles to statute miles) once you’ve taken your speed measurement. Further down the road, you can also use it to calculate your fuel consumption, and if you’re getting bored, conduct long multiplication.

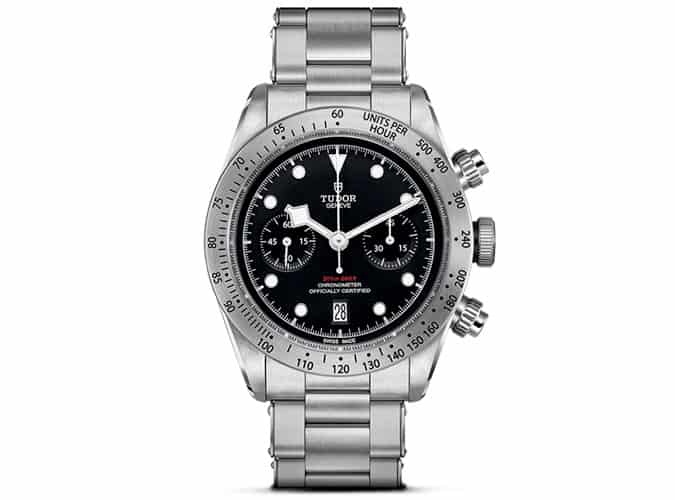

Tudor Black Bay Chrono

Tudor’s Black Bay Chrono split opinion when it launched in 2017; turning a dive watch into a racing chronograph and keeping the iconic snowflake hands (big enough to obscure the chronograph subdials almost completely) rankled with some. But it’s a handsome overall package, and Tudor knows that’s what matters most, to most.

It has a particular appeal if you’re looking to capture a little bit of that Zenith-era Rolex Daytona vibe, as its engraved steel tachymeter bezel bears close resemblance to its 1980s sibling.

Baume & Mercier Capeland Shelby

We’re all familiar with the partnerships between watch brands and carmakers – but in all honesty, some of them are starting to feel a little well-worn. Not this one. Baume & Mercier joined forces with the Shelby Motor Company a few years ago, and while the watchmaker may not have been known for its sporty side, the resulting models have been well received.

They balance the automotive cues (Shelby’s Cobra head on the seconds hand; racing stripes across the dial) with stylish chronograph legibility. And of course, that extends to a tachymeter scale in yellow around the edge of the dial.

Sinn 910 Anniversary

German watchmaker Sinn isn’t the flashiest, or the best-known, but it has a deserved reputation for bomb-proof, practical watches at prices that put others to shame.

The 910 Anniversary chrono is about as flamboyant as Sinn gets, but it’s on our list primarily for functional rather than aesthetic reasons. It’s one of very few chronographs to combine a tachymeter scale with a split-seconds function, which means it can time consecutive intervals. Ideal for, say, logging times and average speeds across both laps of a two-lap race (with a little more mental maths at the end).

IWC Ingenieur Chrono ‘Rudolf Caracciola’

In 2016 IWC began the process of reverting its Ingenieur to a round case shape, away from the Gerald Genta inspired but overly bulky integrated designs of the 2000s. This was one of the first models in the new case, and remains the pick of the bunch; a special edition to honour Rudolf Caracciola, one of the most celebrated Mercedes drivers of the 1930s.

It’s tachymeter scale takes the unusual step of splitting the numerals with a marker for more precise measurement. Good for accuracy, and a bit of a brave decision stylistically.

Christopher Ward C7 Rapide Chronograph Quartz

If you’re looking for a tachymeter chronograph at a sub-£1000 level, your options are not great; most look cheap and plasticky. Almost inevitably, your chrono is going to be quartz-powered at this price level, but if you can live with that, Christopher Ward’s C7 has a more grown-up look in the vein of classic motoring watches of the 1960s and 1970s.

The tachymeter itself is extremely discreet, but it is there, on a thin strip in either black or silver around the outside edge of the dial. We’d avoid the slightly heavy steel bracelet models and go for the aged tan leather strap.