So why has the West suddenly discovered such an appetite for South Korean cinema?

For those who follow the film festival circuit, Bong Joon-ho’s 2019 Palme d’Or win at the Cannes Film Festival for Parasite seemed like an inevitable and justifiable distinction. That the film would go on to win Best Picture at the Oscars, however, was a surprise, specifically because it was the first time in the ceremony’s trenchantly ethnocentric history a film not in the English language won. (It’s one of only three films that won both these awards, the others being 1955’s Marty and 1945’s The Lost Weekend).

Shortly after Bong Joon-ho’s cultural phenomenon, there suddenly seemed an outcropping of Korean appreciation, with Youn Yuh-jung winning a Best Supporting Actress Oscar for Minari (2020) and Netflix’s Squid Game (2021) taking home six Primetime Emmys.

This seeming onslaught of South Korean cinema has been a long-gestating one, and, until recently, surprisingly outside the scope of most major film studios. Unlike the classically acknowledged Neo-realism of Italy, France’s Nouvelle Vague, the German Wave, and so on, South Korea’s generational outbursts of creative cinema have been almost exclusively contained within its own borders.

Part of this cultural growth was due to Japan’s occupation of Korea. The Japanization of Korean culture, which lasted until 1945, led directly to the Cold War politics that divided the country into North and South.

There are only a surviving handful of Korean films made during the Japanese Occupation, before the split on the peninsula, one of the most notable being 1936’s Sweet Dream, which establishes a recurrent theme in the country’s cinema through today, regarding the role of women who often usurp familial control from their continuously emasculated husbands, whose heavy drinking and philandering often stymy them.

By the 1950s, when South Koreans were exposed to Hollywood cinema, a handful of stand out titles utilized melodrama as their way of realism, including Madame Freedom (1956) and Aimless Bullet (1961), both preoccupied with navigating post-war Korea. However, by far the most internationally acclaimed South Korean movie (until the 2000s) would be Kim Ki-young’s domestic disturbance drama The Housemaid (1960), remade by Im Sang-soo in 2010. Ki-young would become one of his country’s most influential auteurs, directing weird, bizarre melodramas metaphorically examining social sentiments through the 1970s and 1980s, when the country’s cinema was hobbled considerably by governmental censorship.

Somehow, Ki-young was able to remake his own iconic title twice, including with Woman of Fire (1971), featuring a young Youn Yuh-jung, and Woman of Fire ’82 (1982). He also made several films revisiting the same subjects, in Insect Woman and the delightfully strange Io Island (1977).

The Housemaid is an excessively perverse drama about a bourgeois family torn apart by a patriarch’s affair, and the dread of discovery by the community at large. In essence, it’s the same kind of transfixing tabloid fodder revealed in the Schwarzenegger-Shriver household.

A handful of trailblazers, classified as the Korean New Wave, from the 1980s, delivered films speaking directly to cultural concerns, and are generally regarded as ending in 1996. But with relaxed censorship and a new governmental push to foster cinematic culture, the late 1990s saw the formation of the prolific South Korean auteurs best known internationally today—the forefathers of the New Korean Cinema. Kim Ki-duk, Hong Sang-soo, Bong Joon-ho, Lee Chang-dong, Kim Jee-woon, and Park Chan-wook, prized hyper-stylized genre films and provocative melodramas. But what’s special about South Korean cinema is how universality is linked inextricably to their cultural specifics (which is why American remakes of New Korean Cinema have failed so disastrously).

Two films represent iconic peaks, both reflecting an intoxicating mix of culturally specific narratives and universal metaphorical distinctions. The first is Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy (Spike Lee infamously remade it in 2013), based on a Japanese manga of the same name. Winning the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival, the second of Chan-wook’s vengeance trilogy finds Choi Min-sik as a drunkard who’s mysteriously imprisoned for 15 years, only to be unceremoniously released from captivity to discover what his past sins resulted in.

Stylized violence and hysterically excessive narrative catalysts create a memorable tale of incest and emasculation, paying homage to Hitchcock and De Palma. The film’s subtexts also suggest Oldboy is an overarching allegory of South Korean cultural experiences, with a captive subject forced to be a silent witness to his country’s political and economic upheavals from the past decade.

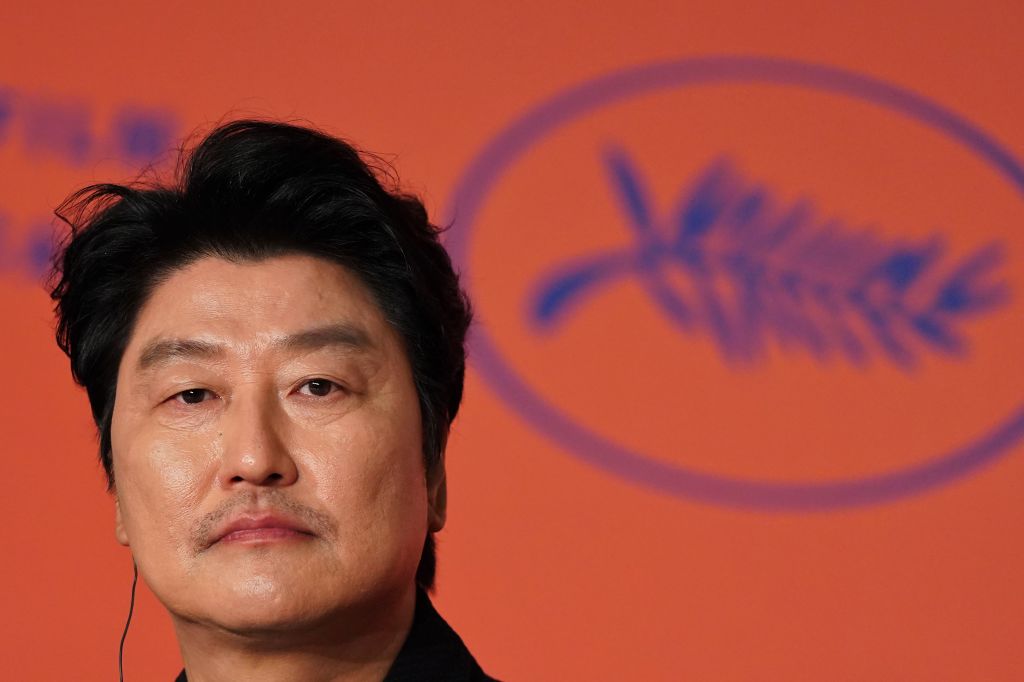

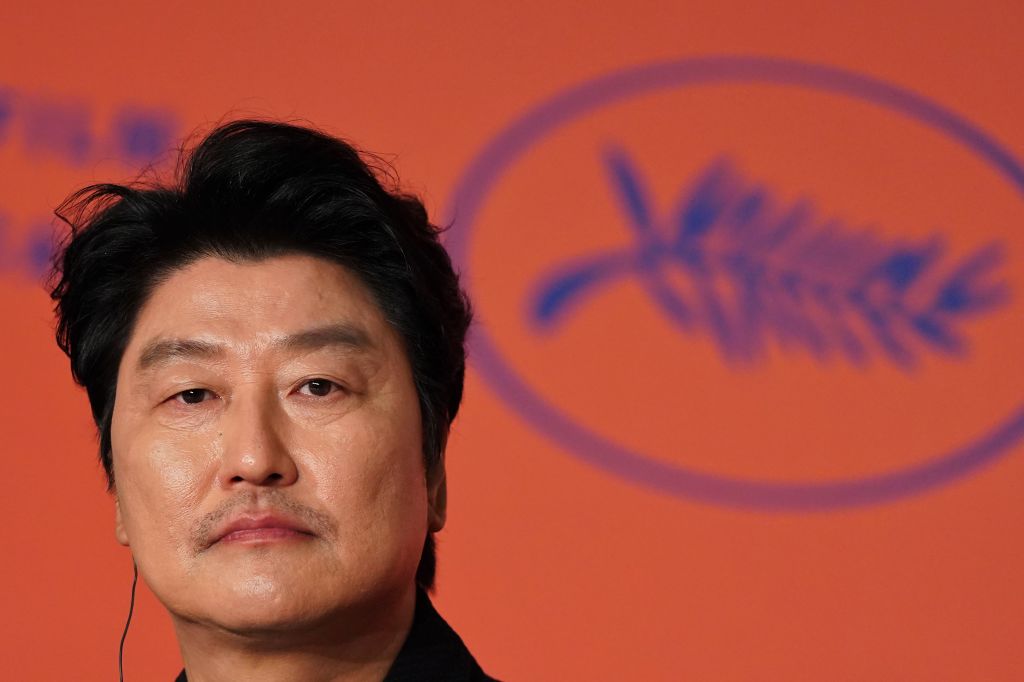

In a sense, Oldboy paved the way for Parasite‘s success. Prior to its premiere at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival, Bong Joon-ho predicted audiences wouldn’t understand explicit cultural elements in Parasite, a black comedy leaning heavily into class hysteria. It finds a poor family forced into the opposite direction of Oldboy, burrowing secretly into an edifice for survival, as their powerlessness suggests it’s easier to feed off the rich as silent counterparts. In an age of absolute visibility, it’s difficult to hide such economic disparities, which strikes into the globalized heart of capitalism’s ills. The family of Parasite, led by South Korea’s greatest contemporary star, Song Kang-ho, jokes about North Korean missiles, a transparent threatening reality that factors into pronounced cultural paralysis. Joon-ho’s massive juggernaut, however, is really an homage to Kim Ki-young’s series of Housemaid films, and reflects the same shifting landscapes without being just a rehash of the same class dynamics.

The unprecedented critical reception of Parasite is perhaps the most significant, cross-cultural acknowledgement of how we’re all universally similar rather than different. While the Golden Age of Korean cinema was heavily influenced by melodrama of the Hollywood studio system (once foreign cinema was allowed to be imported), it’s evolved into its own trendsetting brand of iconicity, even if Western audiences are largely unaware they’re really responding to echoes and reflections of themselves.