Dr. Tom Zoellner is a tenured Professor of English at Chapman University, the author of numerous distinguished works of non-fiction, and an editor-at-large of the Los Angeles Review of Books. Dr. Zoellner has graciously consented to briefly withdraw his critical gaze from classic literature and cast an analytical eye for SPIN at pop and rock lyrics. What follows is a close reading.

In both classic and popular literature the moon is a symbol of transformation. We turn into different people in its alabaster glow; not for nothing did lycanthropes sprout hair in its bath of light, or lovers grow “moony,” while cows leap over it, and Tennyson’s Lotus Eaters gobble their way into an altered state under its full face. When we talk about lunar madness, we are of course talking moonshine.

“The sun gives light; the moon gives illusion,” wrote Roger Wray in 1922. “The sun gives so much light that there is little room left for imagination. We do not easily make legends about the sun; but the moon keeps alive that sense of the mystic without which we might as well be in the prehistoric cave or jungle.”

Understanding this celestial principle is crucial to any exegesis of Pitbull, Ne-Yo, and Afrojack’s “2 the Moon,” which pays obeisance to the titular satellite’s power to make people do strange things.

Part of me wants to leave, take me to the car

Part of me wants to drink, take me to the bar

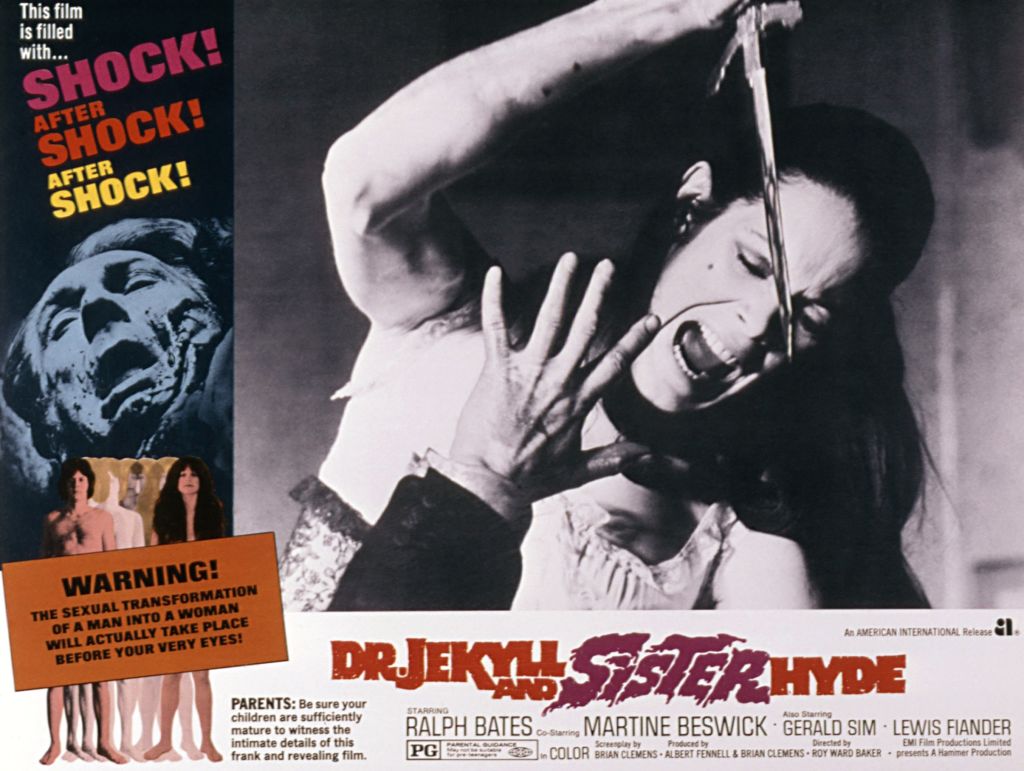

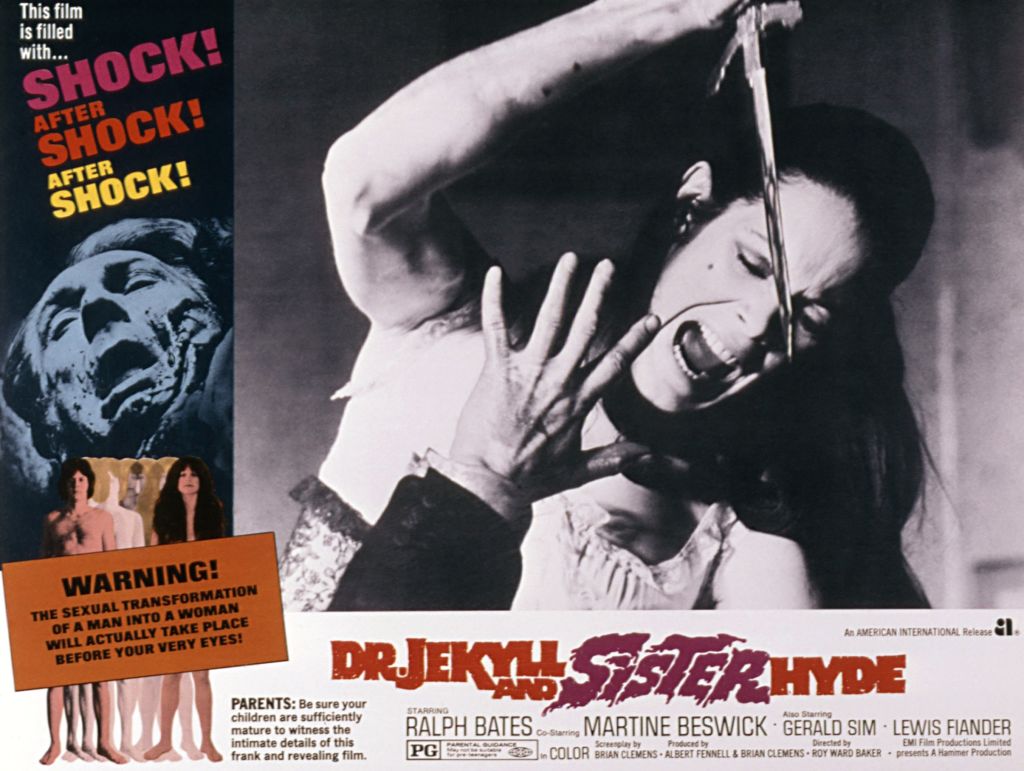

The narrator introduces himself with words of ambivalence. This, no that! He is revealing, immediately, what 19th century theorists called “the man within,” the mysterious alter-ego that yanks us around with irrational demands—what Sigmund Freud would later identify as the Id. Writers of the period were fascinated with it, and not for nothing did Robert Louis Stevenson introduce moon imagery whenever his saintly Dr. Jekyll was about to transform into sinister Mr. Hyde. He writes of “a pale moon, lying on her back as though the wind had tilted her, and flying wrack of the most diaphanous and lawny texture.”

Pitbull and his partners, in their desire to go “2 the Moon,” are a bit more direct but no less literary. They make what seems a conscious echo of Ralph Cramden’s facetious promise to his wife to take her “To the moon, Alice, to the moon”—a signature line from The Honeymooners (there it is again, that old silver coin). And, after some brief debate about getting in the car and going home, they give themselves fully over to the life of instinct and drive, what Freud called the pleasure principle.

I’m a grown man, I ain’t here to play

So don’t talk about it, be about it

Such a giving over to the lunar life is even framed as an existential choice.

This only one life, so live it twice

The listener is then led into an old truism about the moon—a curiosity rooted in physical perspective. While the sun is more than 865,000 miles in diameter, which dwarves the 2,159 diameter of the moon, it lies at such a great distance from the earth that the two appear to be the same size. This optical illusion lends itself to the ancient notion of two “main characters” in the sky, one ruling the day, the other the night. The Greek god Helios trundled the sun along in a chariot, while Selene pulled the moon. They were perfect foils for one another, in terms of light and dark, also symbols for the giving over of the self to hedonism, followed by a return to sobriety and rationality.

The artists say it themselves, and the point could not be more luminescent.

So tonight let’s have some fun, oh

Until the moon turns into the sun