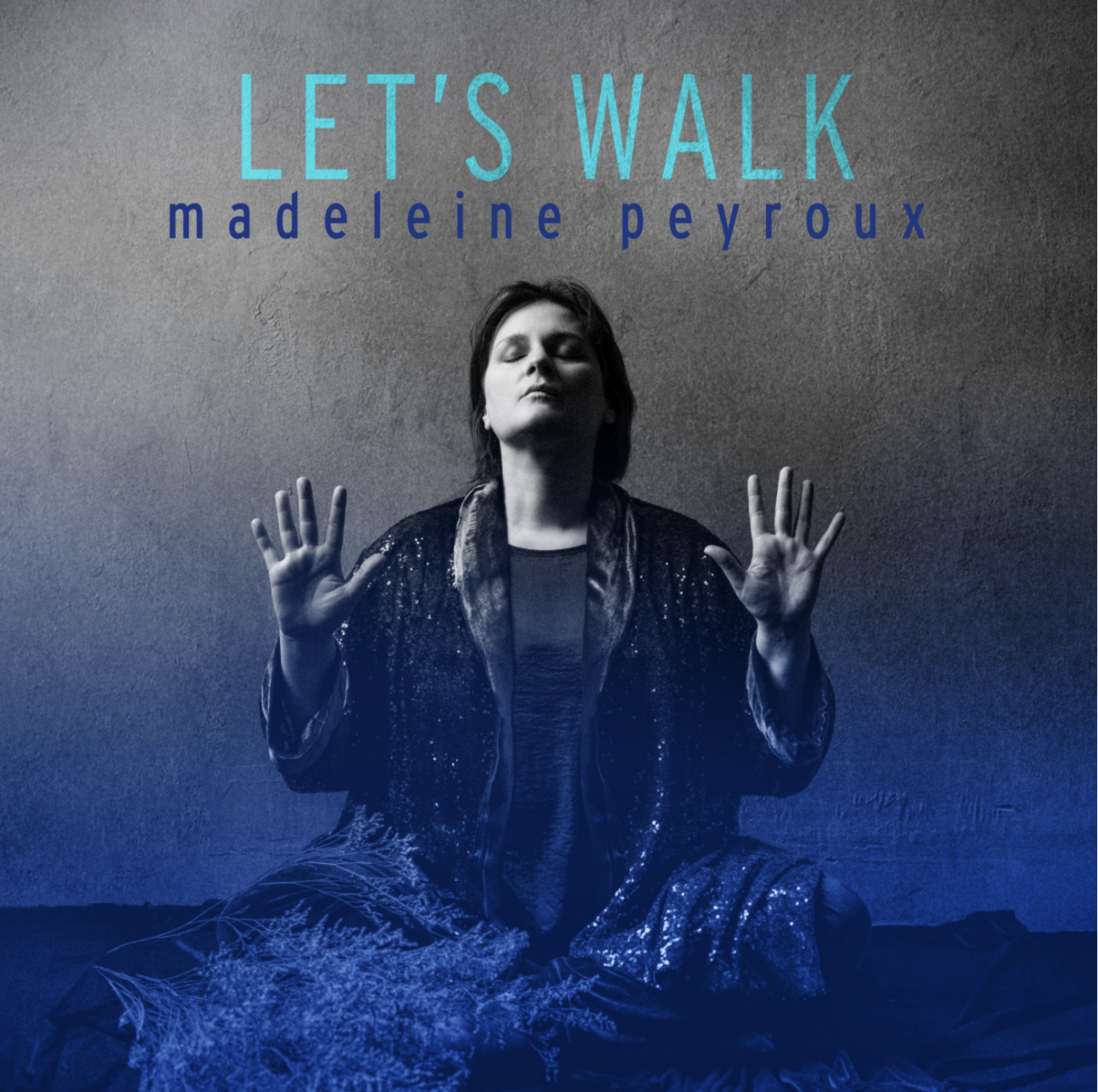

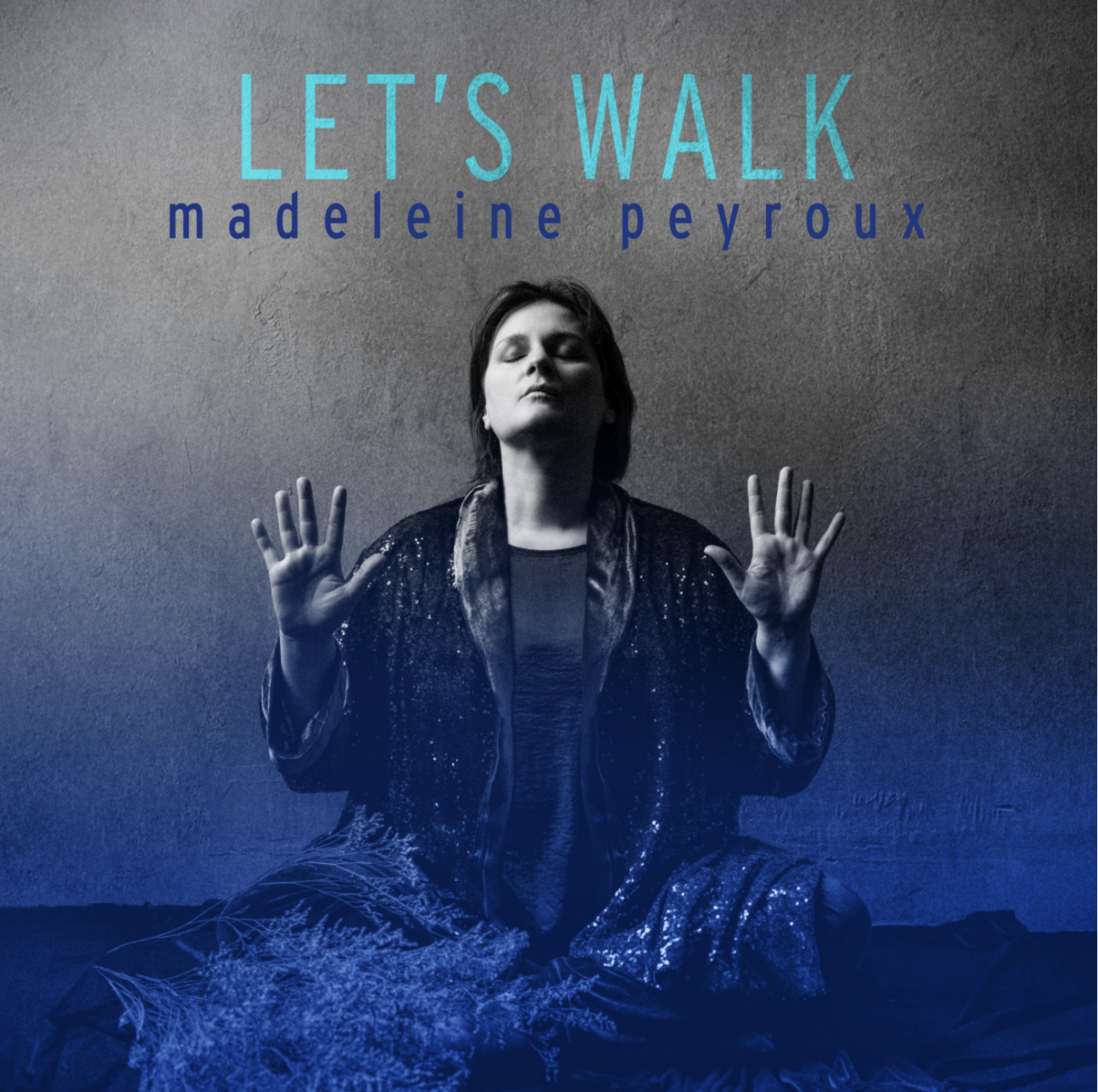

When Madeleine Peyroux was a teenager, she lived a Paper Moon-like existence in Paris with street performer Daniel William Fitzgerald. An experienced musician, Fitzgerald was a positive reflection of “Moze,” Ryan O’Neal’s character in the film. Peyroux stepped handily into the young but quick Tatum O’Neal character, Addie. Instead of pulling scams like Moze and Addie, Fitzgerald and Peyroux played music—with the former doing a much better job as a mentor and father figure than Moze. Decades later, the late Fitzgerald lives on in “Showman Dan,” one of the standout songs on Peyroux’s new album, Let’s Walk.

A modern-day jazz singer in the tradition of the genre’s classic greats, Peyroux tends toward covers. Let’s Walk, however, is all original material Peyroux co-wrote with multi-instrumentalist Jon Herington (Steely Dan). Much like her 2018 album, Anthem, Let’s Walk is an observation on society as much as it is a glimpse into Peyroux’s inner musings.

The sentiments on Let’s Walk are current yet also timeless. They have the romance of jazz standards but the rawness of reality. For Peyroux, this is a major accomplishment, particularly as she was planning on an album of covers with only a few originals thrown in. Producer Elliot Scheiner (Fleetwood Mac, the Eagles) pushed her toward all originals, which turned out to be the right move for Peyroux, nine albums into her long-standing career.

During our conversation, with Let’s Walk still a month out from release, Peyroux is back at home in Brooklyn after a string of tour dates in theaters across North America. Peyroux performed some of the new songs—which audiences were not familiar with—to great reaction. Now that the album is out, Peyroux doesn’t have any shows booked. “Maybe I should look into that,” she chuckles.

How did Let’s Walk come to be an album of all original songs?

Madeleine Peyroux: In 2020, I had the time to write, and I also had time to read a lot. I was forced to be alone with my thoughts and to reach out to people to share my songs with and see what they thought. Jon Herington is the only person who wrote me back and said, “Yeah, that’s interesting.” That’s how we started co-writing in 2020.

You hadn’t written with Jon Herington before?

I’d been on the road with him since 2006 as a touring musician. We’d spent a lot of time being around each other, talking about poetry, talking about literature and lyrics, listening to music. I knew he was interested in writing. I hadn’t had a chance to pursue working with him because we were both already caught up. He was always out with Steely Dan, and if he wasn’t, I would ask him to come out on the road with me.

For me, the thing that’s special about this record, besides the fact that I feel like I finally got to talk about issues in the way that I want to, is the fact that the record was not made because we needed to make a record and make money. It was made because we ended up gathering so much material, and we were grateful for that.

How did Elliot Scheiner get involved?

Jon Herington and I had made a few demos and sent them around. People said “Yeah, I’ll do it.” But there was nobody that had much more of a reaction than that. I felt like I needed somebody to give me some energy. Elliot Scheiner got super excited. He said, “I love the songs the two of you wrote, but all the other ones you have on your list that are covers, I don’t want to do. I think you should write the rest of the record.”

How did that change what you had planned for the album?

That changed everything because we needed time. It had taken me so long just to get to that point. It was late in the year in 2023, and Jon Herington called me and said, “Donald Fagen just called up, and I got to go out on tour.” All of a sudden, energy kicked in. I was like, “We’re recording next month. We’re getting this done before you leave.” I was pushy. Let’s make it happen. And we pulled it off.

How did the recording go?

Knowing that Elliot Scheiner would be there to make everything sound great, I didn’t have to worry about any of that. Jon Herington is this incredible musical director. He had beautiful, tasteful, simple arrangements in mind. We did a couple of rehearsals. We recorded the basic tracks in three days. We came back on a fourth day to put the background vocals together. They sang background vocals on five songs all in one afternoon. It was hectic.

Were there songs that took longer to get over the finish line?

The song “How I Wish” was an epiphany for me. I realized, after rewriting and rewriting, and Jon Herington saying, “No, that was good. What are you doing? Don’t worry. It was all done when you first wrote it, that was it. Stop changing it,” the epiphany was that my job as a writer was simply to try and say what’s already there as clearly as possible. Chip away at the surface of the stone until there’s a shape that’s visible that’s not going anywhere. I woke up every morning focused on that song for a couple of months. It felt like sculpting. That was an epiphany about what good writing might be, at least in my case. I’m not sure that I achieved it, but I had to follow the directions that my higher little voice was saying.

Was that the first time you had that experience?

The trouble I’ve had in the past when I’ve had an idea was the inability to ever really articulate the end result and have people say, “What does that mean?” To me, it was, “Oh, it’s this huge concept. Don’t you get it?” Never stopping to realize that if I’m having to explain that to somebody, I’ve already failed. Go backwards, review, rewrite with the right intention. And sometimes I’ll hit an absolute brick wall.

Were there any songs that were effortless to write?

I woke up with the lyrics to “Let’s Walk.” But I didn’t trust it. That’s one of the big parts of my relationship with co-writers. I sent Jon Herington the lyrics, and he wrote the music. He took what I sent him and sent back a finished song with vocal harmonies and arrangements and everything, three days later. That was magical. I’ve had situations where something comes to me, and I work on it. But the idea of it being fully formed, that’s unusual.

Do you tend to be album-oriented rather than singles-focused?

Yeah. I have wondered about why it needs to be that way. I don’t think we’ve particularly focused on this album as a whole sound. Every song felt so different. But I didn’t want to change anything.

I hope we’re not stuck in an album format in music. It’s too arbitrary to say it needs to be 42 minutes. It can’t be less, and if it’s more, it might be too long. I don’t know how many people listen to albums as a whole record anymore. To me, in the beginning, a record was one side, or four sides. With the Beatles “White Album,” I remember always getting up and turning it again because I can’t live without hearing the whole thing. That record didn’t hold together as an album. It never made sense. It was very odd. But I embraced that record. So I thought maybe there would be a way to embrace this one.

Do you find your audience tends to consume your music as an entire album?

Maybe people that knew my very first record in the 1990s. People now often say I pop up in a playlist. My audience, to date, loves the romantic sound of my recordings, and so I end up being on vocal jazz playlists on different streaming services. The majority of people that are around my age group that are not professional musicians listen to streaming platforms.

Have you been playing songs from the album in your shows this year?

I’ve been playing these songs live ever since we finished making the record. They’ve evolved already to some extent since we recorded it, and the album isn’t even out. The timing didn’t line up because it took us so much longer to make the album. I thought we were going to be able to just start making the record, but we needed almost a year to write.

But I’m so grateful to have been able to play these new songs in all of the concerts that we did starting in March this year. The response has been really strong, standing ovations and everything. At the end of the day, there isn’t anything more important than moments that you have with an audience.