With communities still the grips of the global Coronavirus pandemic, along with the various quarantine measures, people are starting to feel something that seems downright alien to them. For many, it feels like something out of a movie or video game. For some gamers, the series that comes to mind is Silent Hill.

The Silent Hill series has explored a variety of themes, but the ones that stick out (given our current climate) are the themes of isolation and loneliness. To be fair, not all of the entries explore these themes to the same degree, but are still woven into the games. And rather than cover the entire series, many examples of these themes can be gleaned from the first four entries.

Longtime fans of the first game know of Silent Hill’s connections with Adrian Lyne’s 1990 psychological horror film, Jacob’s Ladder. The game contains several references to the film, right down to one of the game’s endings. One commonality is that like Jacob, Silent Hill protagonist Harry Mason loses his child (albeit in different circumstances) and is longing to be reunited with them. All the while, Harry is trapped in the town, with no connection to the outside world. And much like Maurice Jarre’s score for Jacob’s Ladder, Akira Yamaoka’s score for Silent Hill evokes ideas of loneliness. Indeed, the main theme, “Silent Hill”, contains the sound of someone weeping, as if they’re longing for something or someone.

Silent Hill 2, while linked to its predecessor in themes of loss and love, shifts more to a character study. But amongst the psychological themes, there is again at the game’s core, the issues of loneliness and isolation. From the beginning, James Sunderland is grief-stricken over losing Mary, his wife, and is unable to move on. We first find him in the dirty bathroom, staring into the mirror, contemplating while feeling lost. Later on, when he happens upon Mary’s doppelganger, Maria, we see her representing what James longs for in his dead wife (though in more ways than one).

In a poignant conversation (and brilliant symbolism), Maria is found by James in a jail cell. Now, if you’ve played the game, one would realize that Mary was “imprisoned” by her illness. However, when you watch the cutscene, you’ll see that Maria appears relaxed in a rather nice chair, while James appears distressed, and has to use a stool. Not only that, the distance between the two characters from the bars is also telling. Maria, at ease, appears more like she is “visiting” James in jail, whereas James appears more distraught and intense, as if looking for a way out of his “cell”. One could read further into this, as Maria being Mary is something that James could never have, which plays into the loneliness idea.

Moving on to Silent Hill 3, and we see the theme of loneliness expressed even more. Yamaoka’s soundtrack now brings in Mary Elizabeth McGlynn, who provides vocals to songs such as “I Want Love” and “You’re Not Here”, the latter being the game’s “anthem” for many fans. Listening to the lyrics, it’s obvious that the common theme is one of being alone and longing for someone and “save them”. For Heather Mason, the protagonist of Silent Hill 3, that someone is her father, Harry. Of course, if you’ve played the game, you would know that this is not possible.

However, in what can be seen as what happens in real life for many who miss loved ones that are no longer there, Heather eventually finds someone to replace that figurative hole in her life with Douglas Cartland. Granted, there is some “baggage” involved (Douglas is unwittingly part of the reason why Heather can no longer be with her father, after all), but like any good redemption story, the old wounds are healed, and Heather eventually sees Douglas as the father figure she longs for.

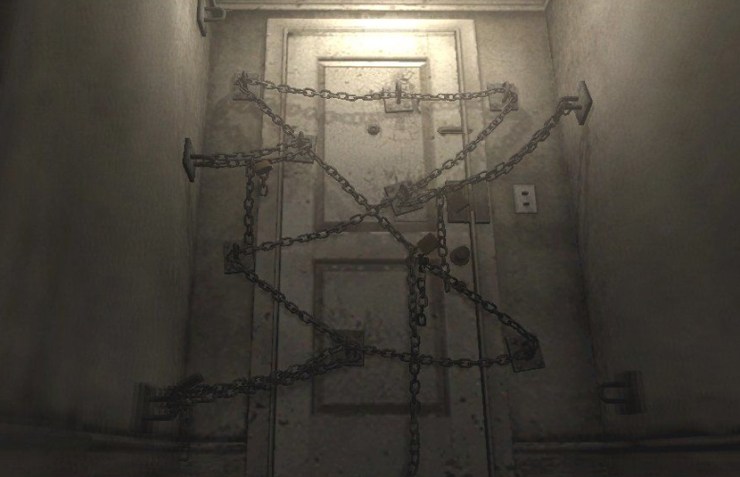

And if you’re going to talk of isolation, Silent Hill 4 is the perfect example. Fans of the series know that this game takes a marked departure from the previous games, but nevertheless retains threads of isolation and loneliness. The most overt example is the titular room.

Functionally speaking, Henry’s apartment contains almost everything that he needs: The game’s sole save point, a storage for excess inventory items, and a few chances to interact with other characters. It’s safe. However, it’s quickly apparent that Henry is literally a prisoner in his apartment. He can’t escape through the door, and no one can visit him. He is essentially in lockdown, much like we currently are. There’s even the ominous warning left by the previous occupant: Don’t go outside. Further driving the idea of isolation are the metaphorical and literal walls between characters. The other residents in Henry’s apartment complex can’t reach once another physically, leaving communication to phone messages and letters, much like our FaceTime or Zoom meetings.

Of course, whenever Henry does have interaction with other characters, it’s through drawing them into dreams. Even in the dreams, Henry still feels isolation from the people he meets (though that’s more owing to his own social issues), preventing him from connecting with any of those characters. This isolation in turn leaves him unable to rescue them from their eventual deaths. Again, it’s akin to reinforcing the public to practice social distancing, lest you end up hurting someone.

Then there’s the voyeurism aspect, where Henry is able to peer out his windows to watch his neighbors, look through the peephole in his door, or observe his neighbour Eileen through a hole in the wall between his apartment and hers. The game eventually forces you to use these viewports to not only advance the story, but also to find solutions to puzzles. Progress (and safety) through isolation.

Eventually, when the pandemic is over, we’ll return to our lives. But things will be different. The normality that we longed for – and the end of isolation and loneliness – won’t be the same as the normality we experience. It’ll still be filled with a lingering fear of other people, resulting in us still seeking to distance ourselves through the same isolation practices as before (albeit not to the same extent). Much like other media that deal with these topics and others like them, the Silent Hill series can be seen as a perverse reminder that as bad as it might seem now, nothing can be as nightmarish as the lonely world we imagine.